Last year Becky Gehrisch chatted with Kathy Halsey here at the GROG about her new book, Escape to Play. She mentioned that she did writing programs with kids for art camps and library programs, so I asked if she'd share some thoughts. She did! Without further ado, here's Becky.

I've had the pleasure of teaching many classes on illustration, art, and writing but one specific example I’d like to share is the “Creating A Picture Book Dummy” class. The first thing I learned is to use any word except “dummy”! Kids just couldn’t get past that! I have renamed it “Get the Picture: How words in picture books are half the story!” A clever or engaging title is a fun way to engage an audience and pique their interest in a talk.

I adapted my writing camp talks to address kids of different age groups from ages 8-17. One set of classes were at the Thurber House, in Columbus Ohio. The Thurber House is a non-profit literary arts center and museum and is located in the home of humor writer - and cartoonist - James Thurber. They offer camps, workshops, author presentations, and other literary events!

Many writing camps and programs have a submission form on their website or at their facility. For the camps I taught, I had seen an advertisement on social media for an upcoming writing camp for kids. I reached out through email and they directed me to the submission form. It was great timing and they liked my pitch!

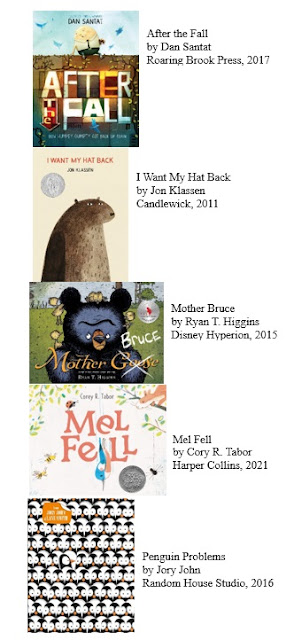

I have found that presenting a slideshow helped the kids who are the auditory and visual learners. I broke down picture books that had great page turn and text placement. After the Fall by Dan Santat is an excellent example. We discussed the placement of text on a page, how words are chosen carefully, and how the illustrations tell half of the story. Good picture book writers don’t describe everything in a picture book.

|

| Becky's list of Great Examples |

I provided many picture book examples which demonstrate excellent storytelling and illustrations, especially those with fine attention to detail in both word choice and imagery. I took the time to read through a few and point out how the words were placed for a specific reason. Then the students could flip through these books during their working time to review how authors and illustrators choose their words and images carefully to further their story. This often included a secondary storyline in images. They saw how the images added to the story more than just mirror what the story was about.

After these exercises, we moved on to tactile learning. To get the creative juices flowing, they could draw from a bowl of prompts for character, setting, problem, and emotion. Some kids had an idea already in mind but others who might be held up by idea paralysis, enjoyed pulling out random ideas to stitch together.

From their prompts and ideas, the students created their own picture book dummy or story. A great resource is Debbi Ohi’s picture book Dummy template. I have used this myself and it was great for kids to see how things are storyboarded. For the younger students, they worked on a larger format to accommodate their fine motor skill development. Students created a quick story and broke down their manuscript by how the words might work best with page turns.

Coming prepared or having the organization provide the supplies and paper gave the kids plenty of choices in how they wanted to express themselves. To keep it simple, we used pencils with erasers if the ideas needed changed. Because time was limited, we avoided colorful writing tools and art supplies to focus on the words. Another class, geared toward illustration, would have an assortment of supplies to show off their creativity.

The camp provided spiral bound writing journals and many kids chose these to brainstorm in. Folded and stapled “dummies” were put together ahead of time for the kids to see how the physical page turns affected their writing.

They could either focus on the writing side more or the illustrative side. There isn’t a right or wrong way. I encouraged them to find the best way that they could share their story. Some did better with images and others by outlining and mapping out their ideas. Folding blank paper helped to show physical page turns.

The kids left the workshop with their own story idea, outline, illustration notes or sketches, and a picture book dummy which gives them a place to start to see how page turns work. Some left with a completed dummy while others just had a writing outline. Either way, they acquired a taste for the picture book writing process. Often, when our time was up, they had a hard time putting their pencils down. Now that was gold!

Teaching these writing camps for kids was such a rewarding experience. Not only was I able to share my knowledge and creativity with the next generation, but I also got to see their creative minds come alive. Teaching camps where kids willingly sign up is heaven. They already came with a passion for writing, so my job was simply to direct them.

Whether you are planning a workshop or looking for ways to engage kids with picture book creation, I hope this can help you organize a successful class!

Thank you, Becky, for sharing your picture book dummy camp ideas. Learn more about Becky at her website, www.gehrisch-arts.com.

.jpg)